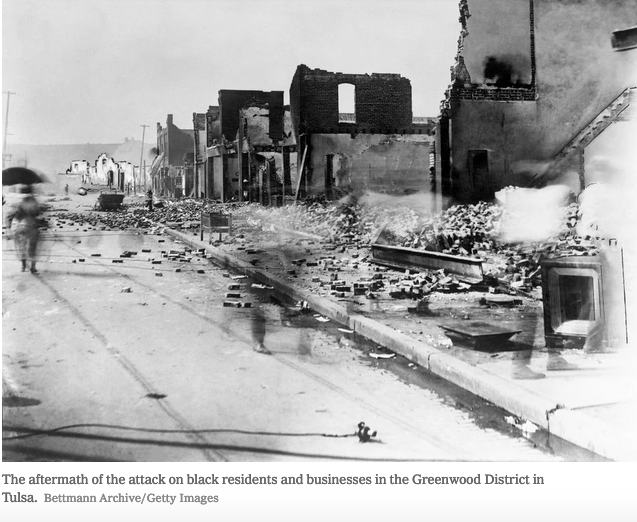

More important than Tulsa’s pop culture moment are the African-American community’s efforts to change the narrative of the massacre that has been ingrained in the city since the last fires of 1921 died out. For almost one hundred years, Tulsa called the events of 1921 a “race riot,” when the city mentioned the event at all. As a kid in predominantly white Tulsa schools in the 1980s and 1990s, I never learned anything about the invasion and destruction of black Tulsa. The silence around the tragedy was broken two decades ago when a state commission was formed to study it. But its first recommendation — reparations to survivors — was never taken up. In 2018, one of the last survivors died, just as the battle over the historical memory of the “riot” became more visceral than ever.

Phil Armstrong wants the new wave of “Watchmen” curiosity seekers to ponder the post-1921 reality. “Not one survivor or business owner was ever compensated for the destruction,” he told me. The commission itself recently replaced “riot” with “massacre” in its name.

The shift in the collective memory is also taking place in local schools, where some teachers still refuse to teach lessons on 1921. The commission has established one- and five-day curriculums about the event, urging teachers to think about it as a massacre, while still giving space for it to be taught as a riot. One lesson plan recommends that teachers tell students “there was an incident in Oklahoma state history, in 1921 in a Tulsa neighborhood. It is known to most as the Tulsa Race Riot, but the survivors refer to it as a massacre.” After the introduction, however, the curriculum defaults to the old way of viewing 1921. “What kind of place was Greenwood before the riot?” the lesson plan asks. “Why do you think that the riot happened? What happened after the riot was over?”

Read full article