As you regroup after the collapse of your bill to repeal the Affordable Care Act, hoping to figure out some new approach to dismember it, you might want to think not about Denmark, but about Rwanda.

Rwanda’s economy adds up to some $700 per person, less than one-eightieth of the average economic output of an American. A little more than two decades ago it was shaken by genocidal interethnic conflict that killed hundreds of thousands. Still today, a newborn Rwandan can expect to live to 64, 15 years less than an American baby.

. . .

One is that it is hard to finance a universal system with voluntary payments. The young and the healthy will be reluctant to pay, leaving only the sick in the insurance pool, which would push the cost of premiums to unaffordable heights and ultimately cause the system to collapse. “No country has attained universal population coverage based on a system organized around voluntary prepayment,” the World Bank researchers wrote.

In fact, they said, in 2012 there were only five countries with more than 600,000 people where voluntary payments accounted for more than one-fifth of total health spending. (The United States was one.) Several developing countries that initially leaned on voluntary premiums to finance their push toward universal health care have turned increasingly to direct government funding, either from earmarked taxes or general budget revenues.

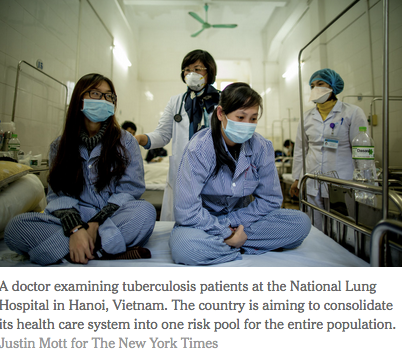

Another rule of thumb is that it is best to consolidate the health care system into one big risk pool for the entire population, as Ghana, the Philippines, Indonesia and Vietnam are aiming to do.

Having several different pools — one for the poor, another for the aged, another for employees of this or that company — blocks the cross-subsidization from the rich to the poor, the young to the old and the healthy to the sick upon which insurance relies. It makes it tougher to control costs, as doctors and hospitals facing a cost-control squeeze in one pool might simply charge more to patients or insurers in the other.

A critical third point is that it will be prohibitively expensive to provide universal health care access without cost controls and mechanisms to pare back unnecessary care. Rwanda, for instance, introduced a results-based financing approach that pays providers based on performance.