His lament resonates far beyond Nordic shores. In many major countries, including the United States, Britain and Japan, labor markets are exceedingly tight, with jobless rates a fraction of what they were during the crisis of recent years. Yet workers are still waiting for a benefit that traditionally accompanies lower unemployment: fatter paychecks.

Why wages are not rising faster amounts to a central economic puzzle.

Some economists argue that the world is still grappling with the hangover from the worst downturn since the Great Depression. Once growth gains momentum, employers will be forced to pay more to fill jobs.

But other economists assert that the weak growth in wages is an indicator of a new economic order in which working people are at the mercy of their employers. Unions have lost clout. Companies are relying on temporary and part-time workers while deploying robots and other forms of automation in ways that allow them to produce more without paying extra to human beings. Globalization has intensified competitive pressures, connecting factories in Asia and Latin America to customers in Europe and North America.

“Generally, people have very little leverage to get a good deal from their bosses, individually and collectively,” says Lawrence Mishel, president of the Economic Policy Institute, a labor-oriented research organization in Washington. “People who have a decent job are happy just to hold on to what they have.”

. . .

In 1972, so-called production and nonsupervisory workers — some 80 percent of the American work force — brought home average wages equivalent to $738.86 a week in today’s dollars, after adjusting for inflation, according to an Economic Policy Institute analysis of federal data. Last year, the average worker brought home $723.67 a week.

In short, 44 years had passed with the typical American worker absorbing a roughly 2 percent pay cut.

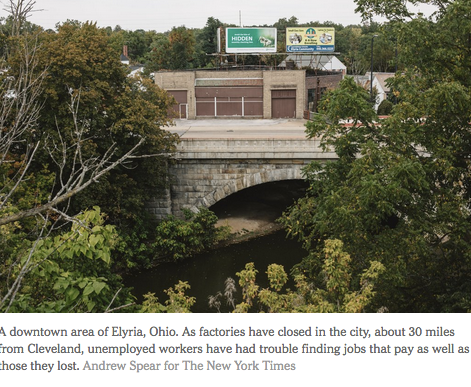

The streets of Elyria attested to the consequences of this long decline in earning power.