A hundred years ago this week, on a bend of the Meuse River in northern France, Gen. John Pershing launched the final major Allied offensive against Germany, an assault that would bring an end to World War I two months later.

Without American intervention, the war would have probably ended in a German victory, or sputtered to a stalemate, leaving the Germans in possession of much of France, Belgium and Russia. The victory, though, came at significant cost: In the Meuse-Argonne offensive, as the operation came to be known, the Americans alone suffered some 122,000 casualties, including 29,000 dead.

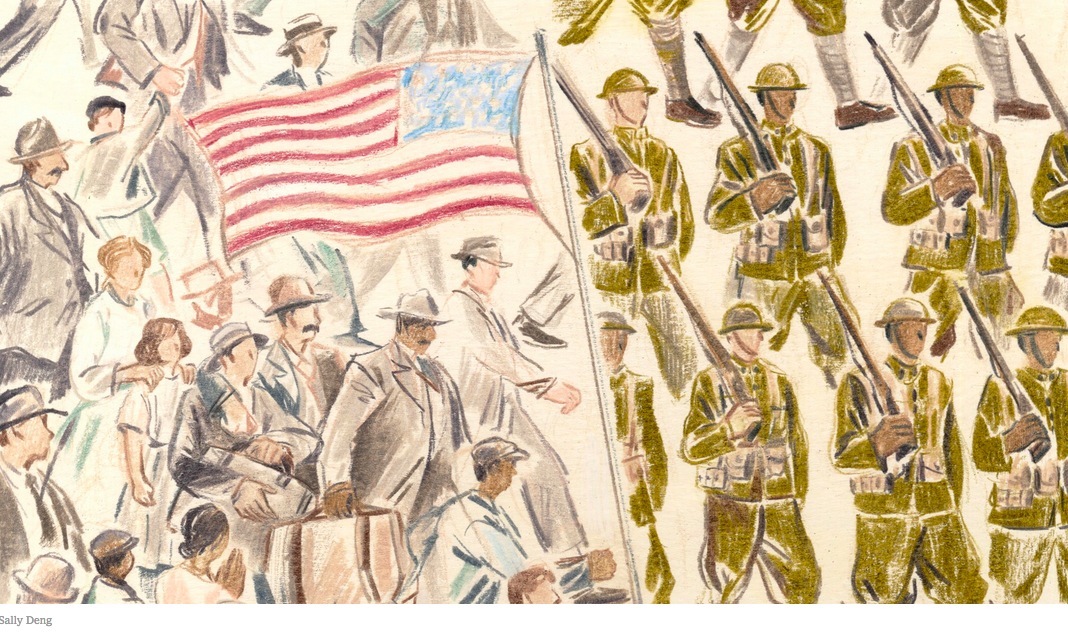

That more than a million Americans were fighting in a European war was surprising enough. But even more surprising was the men themselves: Pershing’s soldiers, known as the American Expeditionary Force, were in some units as likely to be foreign- as American-born.

Thanks to a wave of immigration, the United States had changed significantly at the turn of the 20th century, going from a nation whose white population was 60 percent British and 35 percent German at the start of the Civil War into a turbulent “melting pot” in time for the Great War: 11 percent British, 20 percent German, 30 percent Italian and Hispanic and 34 percent Slavic.

. . .

How did this “half-American” army do in World War I?

They were splendid. Even though the doughboys spoke 49 different languages, making training and command difficult, the immigrants fought as bravely and desperately as native-born Americans. Germans deployed against the United States 77th Division in the Argonne Forest, hearing the mix of voices from the other trench, assumed that they were fighting Italian troops who had been sent north to reinforce the French. They weren’t Italians; they were Americans, from Little Italy in Manhattan.

The Germans were fascinated by the Americans they captured on the battlefield. The Germans had assumed that with all its immigrant soldiers the United States Army would shatter into demoralized ethnic pieces when pressured. “The majority of them are the sons of foreign parents,” a German staff circular reminded interrogators. But German hopes of disintegration were dashed on the battlefield. “These half-Americans express without hesitation purely native sentiments. Their quality is remarkable. They brim with naïve confidence,” the Germans despaired.