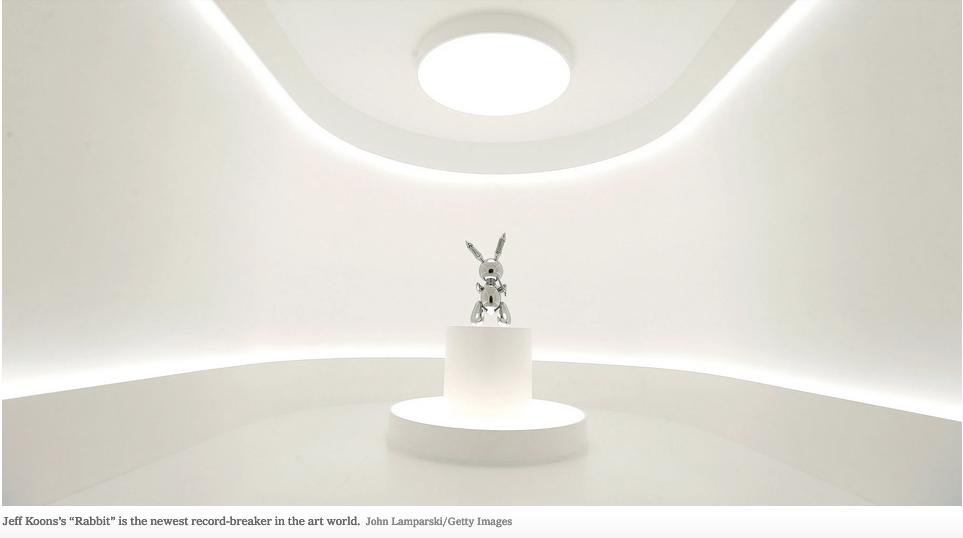

The art market has a 0.01 percent problem. That much was apparent on Wednesday at the contemporary auction at Christie’s in New York, where a stainless steel rabbit by Jeff Koons sold for $91 million, setting a record price for work by a living artist. If it seems as if these sorts of records seem to be set much more often these days, it’s because they are — just last fall a David Hockney painting sold for $90.3 million, the previous record for a living artist.

Art collecting has always been an exclusive activity, but the world of contemporary art, in particular, has become dominated in recent years not by the 1 percent — the millionaires — but by the super-wealthy billionaires of the 0.01 percent.

This growing inequality threatens to upend how the market works. The small and midsize galleries that have long supported and nurtured unknown artists are finding it difficult to survive in the winner-take-all economy of contemporary art, meaning the next Andy Warhol or Donald Judd, who rose through the ranks of the gallery system, might never be discovered.

The art market reflects and magnifies trends in the larger economy. Recovering even faster than G.D.P., annual sales in the American market have more than doubled since the global financial crisis. According to a 2019 report published by Art Basel and UBS, in 2018 art sales reached nearly $30 billion, compared with just over $12 billion in 2009.