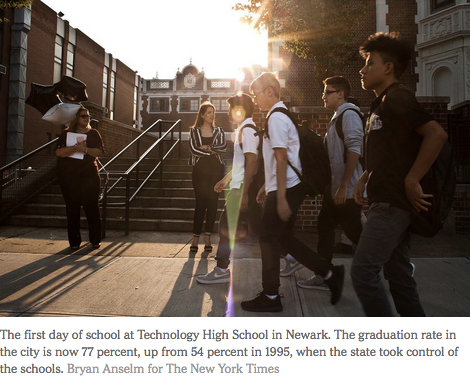

Newark’s schools have improved — the high school graduation rate is now 77 percent versus 54 percent in 1995; on state tests, the district now ranks in the top quarter of comparable urban districts; low-performing schools were closed while charter schools expanded. The district is retaining more of its best teachers, and fewer of its least effective ones.

But the decision to give authority back to the city is in many ways a recognition that state control is an idea whose time has passed. Around the country, 28 other states enacted similar policies, fueled by a desire to hold districts more accountable. Many of the districts taken over were in heavily minority low-income cities. At present, around 60 districts are under some form of state management, said Kenneth Wong, chairman of the department of education at Brown University.

When New Jersey took over the schools, it was thought of as an emergency intervention. In evaluating the legacy of state control, Paul L. Tractenberg, an emeritus professor of law at Rutgers University, said that the idea went “badly off the tracks” by failing to provide sufficient funding and turning into a “really endless state operation.”