When Tanya Brice’s mother moved into her apartment in Owings Mills, Md., five years ago, she was already caring for twin toddlers, one of whom has autism and an intellectual disability, and a teenage son. Brice, 43, is a single mom, and was supporting the household on a social worker’s salary. Her budget and schedule were stressed to the breaking point.

Her mother, Janice, was medically fragile — she had hepatitis C and diabetes — and Medicaid wouldn’t pay for a home health aid, so that came out of Brice’s pocket, along with the money for higher electricity bills from her mother’s ventilator, and the extra food and necessities her mother needed.

“There was no money,” Brice said. She tried to cover “rent, utilities and food,” but cable, extracurricular activities and “everything else went by the wayside.” Sometimes, there wasn’t even enough food to go around.

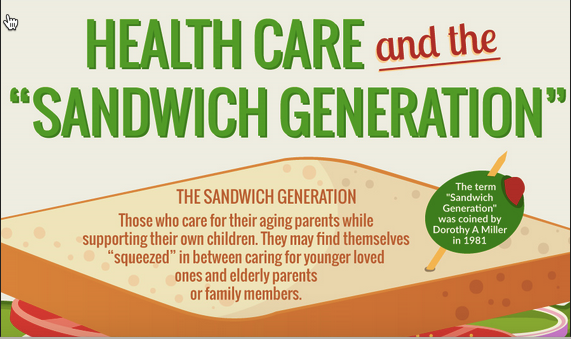

Brice is part of what demographers call the “sandwich generation” — a group of Americans who are caring for children under 18 and older relatives at the same time. Twelve percent of parents are part of the sandwich generation, according to data from the Pew Research Center. Sandwich generation parents who are between 18 and 44 are spending about three hours per day on caretaking, compared with similar parents over 45, who do closer to two hours per day. This difference is likely because the younger parents also have young children.