Detroit is stuck. Its carmakers still sell plenty of vehicles. But while their chief challenge for the past century has been figuring out which cars consumers will buy, they now face a future of having to sell Americans on the very idea that they need to buy a car at all.

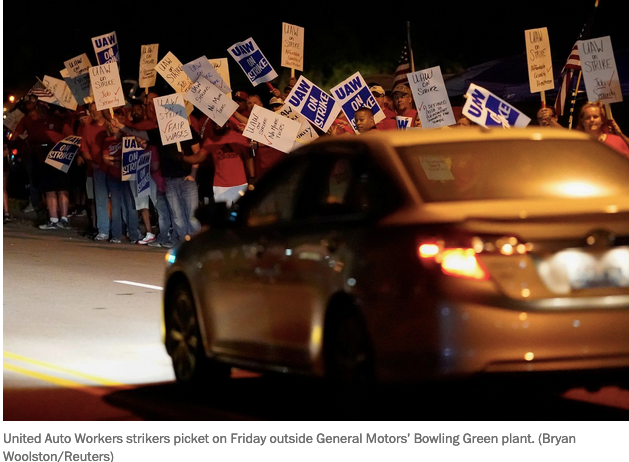

That’s what makes the United Auto Workers strike against General Motors so different from past conflicts. The union and carmakers have always played tug-of-war: In good years, the UAW demands a share of the prosperity. In bad years, the companies seek concessions so they can stanch their losses. But the current strife pits the auto industry’s past way of doing business against its uncertain future. The carmakers would have you think that every American wants a big ol’ SUV or pickup truck. And the union, with its walkout, is saying it wants to keep things the way they are, without shutting plants or laying off workers or paying more for health care.

But the stakes have changed in a way that neither the carmakers nor the union fully acknowledges. Consumers have signaled that maybe they don’t need Detroit quite as much as they used to. Auto analysts suggest that the country has reached “peak car” — meaning the number of autos sold each year isn’t likely to increase. Some predict a drop in worldwide demand. The long-term trend has been shifting toward fewer cars per household. Because the United States is so big, it takes a lot to bump the ownership statistic, but it has been below two cars per household since 2009. Not only do these trends cause havoc with automakers’ planning, they blunt the UAW’s ability to argue for more money and guaranteed jobs, and to get them through strikes.