If you’re curious how Republican legislators in Wisconsin rationalize passing last-minute legislation aimed at hobbling the state’s governor-elect, Tony Evers (D), allow them to explain.

“Listen. I’m concerned,” Senate Majority Leader Scott Fitzgerald said at a news conference on Tuesday. “I think that Governor-elect Evers is going to bring a liberal agenda to Wisconsin.”

If the legislation isn’t passed, Wisconsin State Assembly Speaker Robin Vos (R) warned on Tuesday night, “we are going to have a very liberal governor who is going to enact policies that are in direct contrast to what many of us believe in.”

The fear, from the top-ranking Republicans in the state legislature, is explicit: They are worried that Evers will advocate for policies and actions that are at odds with a conservative agenda, that he’ll make decisions that Republicans — “many of us” — disagree with.

Well, yeah. That’s how elections work. The person who wins more support from the state’s voters gets to run the state. Many of those voters won’t be happy with those decisions, but more of them, presumably, will be. Arguing that the power of the governor must necessarily be curtailed because a candidate won an election and will advocate the positions he ran on fundamentally goes against the spirit of democracy.

But the problem here isn’t only with how Fitzgerald and Vos are reacting to Evers’s win. Another problem is that the gulf between the two parties on policy issues has never been wider. Another is that elections have often become fights between two electoral poles instead of moderated appeals to unity.

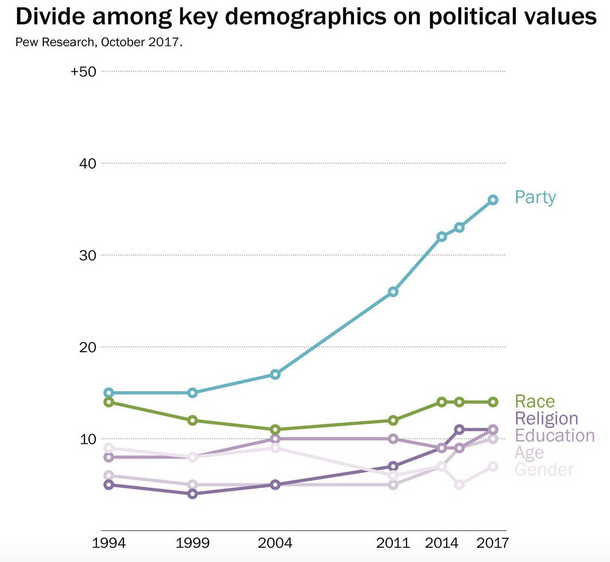

To the first point, we can look at data provided by Pew Research Center polling. Pew has tracked opinions on 10 policy issues since 1994, including things like corporate profits, race, homosexuality and government. The gaps on views of those issues were about as wide between racial groups in 1994 as between members of either major political party. In the years since, though, that latter gulf has widened dramatically.