This week, a team of economists led by Raj Chetty of Harvard University released a massive new data set on prosperity at the neighborhood level in the United States. Called the Opportunity Atlas, the data builds on Chetty and company’s previous work on inequality and opportunity, tracing, block by block, how the environments children grow up in shape who they become as adults.

Much of the focus in media and policy circles has been on the plight of children from low-income families, and the social and economic barriers preventing them from pulling themselves out of poverty. But the data released this week strongly suggests that the same forces holding lower-class kids back are creating difficulties for middle- and upper-class families, as well.

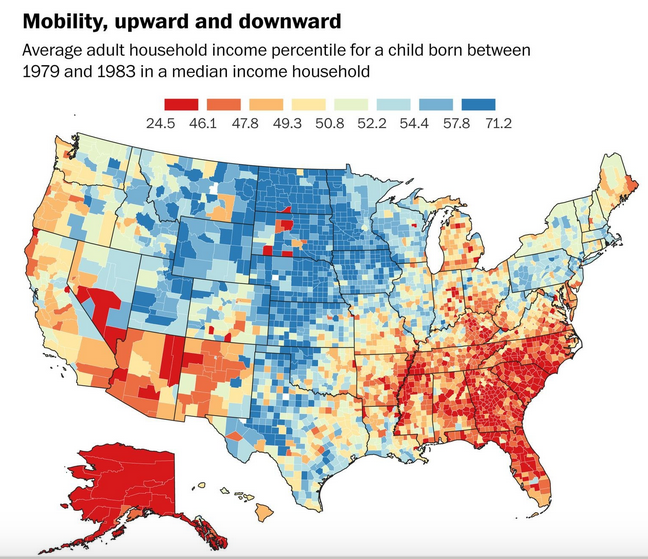

Consider, a child born between 1979 and 1983 to a middle-class family with an income right in the middle of the U.S. income distribution — what economists call the 50th income percentile, or about $55,000 in 2015 dollars. Because family income has a huge effect on children’s eventual outcomes as adults, we’d expect that child to end up more or less in the 50th income percentile when they grow up.

At the national level, that’s true: The average child born to a 50th percentile family in the early 1980s ends up exactly at the 50th percentile today. But if you drill down beyond the national average, you find that children’s outcomes vary significantly by where they grew up. In some parts of the country, middle-income children tend to end up much higher in the income distribution than their parents’ level. In these places, the dream of ending up better off than your parents is still very much alive.

In other places, however, middle-income children tend to end up worse off than their parents. Sometimes, significantly so.