WASHINGTON — An unprecedented expansion of federal aid has prevented the rise in poverty that experts predicted this year when the coronavirus sent unemployment to the highest level since the Great Depression, two new studies suggest. The assistance could even cause official measures of poverty to fall.

The studies carry important caveats. Many Americans have suffered hunger or other hardships amid long delays in receiving the assistance, and much of the aid is scheduled to expire next month. Millions of people have been excluded from receiving any help, especially undocumented migrants, who often have American children.

Still, the evidence suggests that the programs Congress hastily authorized in March have done much to protect the needy, a finding likely to shape the debate over next steps at a time when 13.3 percent of Americans remain unemployed.

Democrats, who want to continue the expiring aid, can cite the effect of the programs on poverty as a reason to continue them, while Republicans may use it to bolster their doubts about whether more spending is needed or affordable.

“Right now, the safety net is doing what it’s supposed to do for most families — helping them secure a minimally decent life,” said Zachary Parolin, a member of the Columbia University team forecasting this year’s poverty rate. “Given the magnitude of the employment loss, this is really remarkable.’’

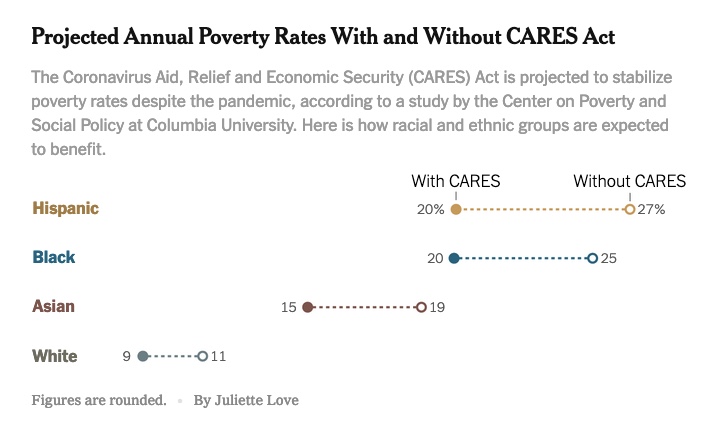

The Columbia group’s midrange forecast has poverty rising only slightly this year to 12.7 percent, from 12.5 percent before the coronavirus. Without the Coronavirus Aid, Relief and Economic Security Act — the March law that provided one-time checks to most Americans and weekly bonuses to the unemployed — it would have reached 16.3 percent, the researchers found. That would have pushed nearly 12 million more people into poverty.